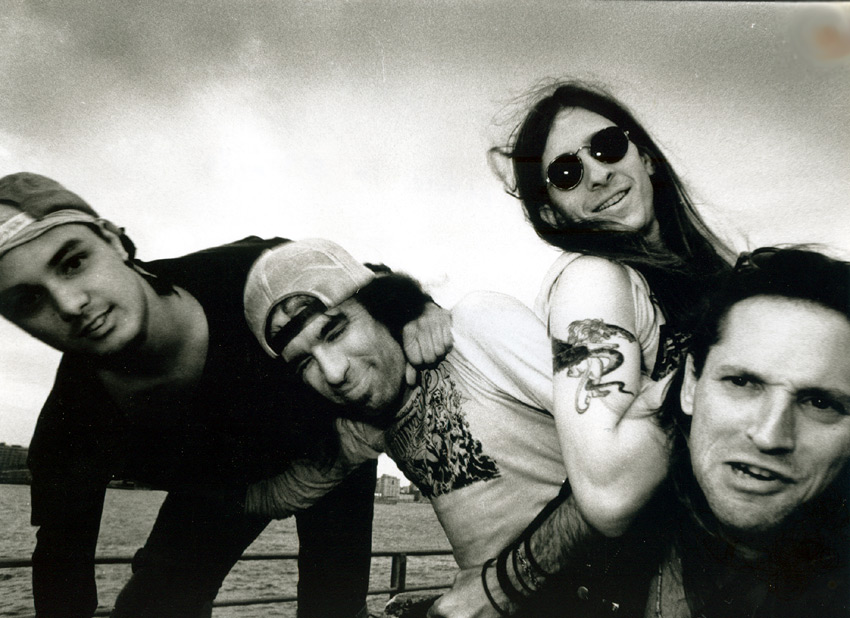

The process of creating legendary Deep Six compilation and its today’s meaning, Skin Yard and its related plans, C/Z Records label, Seattle music scene, a great boom for grunge and what has been left of it – this is what we talked about with Daniel House – the co-founder and bass player of the Skin Yard, as well as the long-time president and owner of aforementioned C/Z – a Seattle-based independent record label, whose logo signed the albums of bands like, among others: 7 Year Bitch, The Gits, Hammerbox, Love Battery, The Melvins and The Presidents of the United States of America.

Polish version below/Polska wersja niżej

The Deep Six compilation has become legendary for the Seattle music scene as one of first and one of the most important records in the history of grunge. It had its 35th anniversary on March 21…

It has been 35 years already? Wow. I know it’s important historically but for all of us who were there, well…none of us thought that we were doing anything that was some kind of big thing. It was a very small scene at that time, there weren’t too many bands and there weren’t too many clubs, the audience was all of our friends and we would all go to each other shows. We were all in our late teens or early 20’s so we were just playing music and having fun. There were only 2 bands on the compilation that actually had released something previously: one was Green River and second was the U-Men.

With such perspective of time – 3 and a half decades later – how do you evaluate this album? From both points of view – a musician who was involved in the project and a man who was later the head of C/Z Records – the label which released this compilation.

On the one hand Deep Six was the first record that put a marker in the ground saying this is the beginning of something that’s happening, but – as mentioned – we weren’t intending to do it that way, it just happened. I assume that you know that I’m not the one who put out Deep Six.

Yes, I know that it was started initially by Chris Hanzsek and Tina Casale.

Exactly. So, when it came out not that many people bought it. There were 2000 copies and I think everybody in the various bands got maybe three or four each. Probably in Seattle maybe another 200 were sold and that was pretty much it. People outside of Seattle didn’t know any of these bands. Chris also had started the studio at that time and he had all these boxes of records stuffed underneath his bed. Nobody was buying them; he was maybe selling 5 or 10 at a time at record stores. He spent a lot of money putting together the recordings and putting together the pressing and he realized pretty quickly that he had no interest in running a record label anymore. These were the early days of Skin Yard and I was very interested in recording and releasing music. While Chris had a waning interest, I had a lot of it, so I basically took over the label from him, bought all of the inventory, all the records and I preceded to work on selling them and getting distribution. I think it took me probably 3 or 4 years to finally sell through most of those records. Even though it was probably only 700 or 800 left, it took that long. Now I still have about 10 or 12 copies and I can sell them for $350.00 apiece. Now everyone wants to have it. So, from business point of view, it became successful, but it would be many, many years later. And from music point of view, well… most of all, I think it’s a very important document. With one exception – my own band. Skin Yard was probably the youngest band on the compilation, we had barely been around at the time and I guess we were still figuring out who we were as a band. Our Deep Six recording is the only Skin Yard music that makes me cringe when I listen to it. On the one hand, I’m very happy that we’re on that record because I think if we hadn’t been there, it may have written our place in music history differently. We may not have been considered as important to that scene. On the other hand, I wish nobody could hear it, because I think it’s terrible.

I don’t think it’s terrible.

You’re so kind, but I can’t help it, I think it is. It doesn’t seem a lot of people think that. But you know, our singer really hadn’t figured out how to sing yet. I think there are 2 bands on that record that don’t really quite make sense and don’t really fit on: that’s us and also – The U-Men. They were very distinct and it’s part of why they were so popular. There was nobody else in Seattle that sounded like what they were doing. The only band anywhere that you could compare to them is maybe The Birthday Party or maybe a little bit of The Gun Club.

Looking back then, with the knowledge and experience that you have now, would you do something in a different way with Deep Six promotion?

I probably wouldn’t do anything different because when Deep Six came out it was just a document of little, teeny tiny music scene in a city that nobody cared about until certain bands started to get signed on major labels. So, I guess I would talk about what the music world was like before the World Wide Web and how the Web changed everything. Before the World Wide Web, there could be regional scenes in different cities in America and in probably cities all across Europe as well, that would develop very organically. That things could happen in relative isolation. In America we had a Seattle scene, but we also had scenes in New York City that was totally different, with bands like Live Skull and Sonic Youth. A lot of people call them No Wave, but it was kind of noise rock. There was a different scene in Minneapolis, there was a different scene in DC with the whole Discord label and bands like Minor Threat and then another scene in Athens, GA, which was totally different.

And then the World Wide Web came around…

And suddenly everybody can start to hear what everybody is doing anywhere in the world, so now everybody can be influenced by other things in a real time. I don’t know what’s happening in Poland musically but if I wanted to find out I could probably look it up and figure it out pretty quickly. On the one hand, it’s kind of cool but on the other hand, it kind of kills the ability for things to develop organically and naturally. And to me, that’s somehow disappointing. It makes it much easier for people to promote things, but it also means that natural art scenes can’t happen the same way, so it’s a double-edged sword. I think that Seattle will prove to be the last organic scene of this kind. Getting Deep Six heard nationally took the time that it took because there was no World Wide Web so it was a very slow process. And, in a meantime, the bands on that record continued to release more music. As Skin Yard we made more music, Soundgarden made more music and Soundgarden were of course part of the reason why the scene became big and exploded, certainly. The U-Men put out more records as well. I think Malfunkshun was probably the one who broke up the earliest but then from there, you had bands like Mother Love Bone. And then people discovered Mother Love Bone, again on a major label, and then they go back in time and start digging around to find out who the band was before. And then they discovered Deep Six.

At that time Deep Six sales were decent in and around Seattle but nationally the record sales results were rather a disappointment. Now it’s one of the most wanted albums for Seattle sound fans, all over the world. It was re-issued in 1994 but it’s still almost impossible to get this album. Is there any chance that there will be some additional re-issue, for instance for its 40th anniversary?

I don’t think so. The reason why A&M Records re-issued it in 1994 was because Soundgarden had been signed to A&M Records and they wanted basically secure the rights to miscellaneous Soundgarden recordings if they could: they wanted to be able to control all of it. So, what they did is they offered to buy the rights to the record. They didn’t care about anybody else. At that time Susan Silver said to me something along the lines of: “they are willing to buy the record from you for a decent bit of money and if you don’t do that, they’re willing to basically take it away and you’ll get nothing”. There was a legal team in A&M, and their perspective was: “your contract isn’t any good and we can take it away, and there’d be nothing you could do.” Susan knew that it wouldn’t be fair, so she worked something out. Eventually we’ve got some money and put in the contract that A&M will release it actually on CD (as it had never been on CD before). They did it but didn’t really do much to promote it. I don’t think most people in A&M Records today even know what Deep Six is and I don’t think they could really get away with releasing it unless every band agreed to do that. It would probably cost too much, and I don’t think they really care. That’s not how major labels works. And I can’t release it by myself because I sold the rights.

How do you recall the process of creating Deep Six and the two-night release party at UCT Hall on March 21 and 22, 1986?

I believe I was the one who actually talked Chris into getting The U-Men on the record. They didn’t really want to be on it. I just said to Chris: “they’re the biggest local band right now and you kind of need to have them, because if you don’t, you’re going to have a hard time selling the record.” Well, he had a hard time selling the record anyway, but without them it would be even harder. Each band spent two days in the studio and one person from each band was allowed to be there during mixing, the whole band wasn’t allowed to come in. From Skin Yard it was Jack Endino, who was already our engineer, so it made sense, from Green River I think it was Jeff Ament, from Melvins it was probably Buzz Osborne, from Soundgarden I’m not sure if it was Chris or if it was Kim. About the concert I have limited memories because it was a very long time ago, but I know that I was involved with putting together the show and that I designed the poster. I kind of co-promoted it with somebody but can’t remember who it was, maybe you know from the research?

Unfortunately, I’ve been looking for this information but haven’t found it.

Well, I really don’t remember. Anyway, 6 bands were too many bands to put on one night, so we made it into a 2 night affair. It wasn’t just a show, it was an actual event. We had a limited number of tickets for each night and every band had a limited number of spots on their guest lists. We figured out how to put together the shows for each night. The second night was Malfunkshun opening, then us and then U-Men headlining and on the first night, if I’m not mistaken, I think it was Soundgarden first and then the Melvins and then Green River.

According to the poster it was exactly this order on your day and Melvins, then Soundgarden and Green River as a headliner on day 1.

Oh yes, right. Both nights were sold out pretty quickly and most of the same people were there for each night. Both gigs were really very intense, very loud and it was totally exciting because it felt like “something was happening.” I think it helped to cements everybody that played those two nights as being kind of the preeminent bands. We were the bands that were representing this new thing that was starting to happen. Like I said, nobody was “trying” to make it happen, it was all very organic. Before that it was a little more art rock, a little new wave and maybe some rockabilly, and suddenly there were these bands who were beginning to play harder, heavier, louder, and dirtier.

John Peel in The Times of London called Seattle sound “the most distinctive American sound since Motown”. What do you think – where did this grungy, heavy sound come from? What’s the background of this specific sound?

It’s a wonderful compliment but I don’t think that most of us, people in the bands, would agree that it was one of the most distinctive sound since Motown. Everybody was pulling from a lot of the same influences; we were being influenced by bands that came before us. That whole scene was pulling from hard rock, arena rock and then underground, slightly more obscure stuff. On the arena rock side, you can hear there’s a lot of Black Sabbath influence for instance. There’s some Aerosmith with Green River – they were absolutely influenced by The Stooges but also by Aerosmith. Bands like Soundgarden and Melvins were probably influenced a little more by Black Sabbath, but then there are more underground bands that came from that scene that you know from hard rock. Way back then Skin Yard probably had more influence from bands like King Crimson. I suppose The U-Men were influenced by The Birthday Party and other bands like that. But, in general, we were all influenced by things that came before us and a lot of us listened to the same music. A lot of us grew up in high school listening to early AC/DC, Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin and Aerosmith but also bands like The Stooges and MC5. There were more obscure bands for people that were really digging more deeply into the early 70’s and maybe the late 60’s so there’s probably some influence from garage rock stuff things like The Sonics and The Wailers. And then just some of the heavier psycho stuff that was maybe coming around out of Detroit, even bands like – I can’t stand him as a human being, he’s a horrible person, but his first records are fantastic – Ted Nugent and The Amboy Dukes. So, bands like that as well. We’re definitely influenced a lot of what we’re listening to, and I think it was kind of at the same time, you had early records by Sonic Youth and Bad Brains. We were like sponges that were taking it all in and we were chewing it all up and then we were kind of reinterpreting it, reimagining it in our own way. But I think you hear a lot of similar things in a lot of the rock that was coming out of Minneapolis at the same time, like early The Replacements. Although maybe that was a little more punk influenced and we maybe were influenced more by the heavier stuff.

And you personally? Which bands influenced you the most?

There’s so many, let me think about… Just to name a few, back then I was probably more into Led Zeppelin then into Black Sabbath. There was one British band that most people in the US don’t know that influenced Jack Endino specifically, and then later me – The Groundhogs. And another band from London – King Crimson. Some Bauhaus even. Seattle at that time was kind of dark and kind of dangerous, so the city itself for sure also had some impact on our sound. We were also pulling from bands like Killing Joke and The Stooges. I think that Seattle rock actually did a lot to help create more awareness around the early The Stooges records, they’re bigger now than they were when they came out. When they just came out nobody cared because they were too outrageous for what was going on at the time. And now? Now people look back at them and they worship them as gods because actually yes, they were kind of gods.

How would you rate the impact of Deep Six on PNW music scene?

I don’t think that Deep Six record itself was necessarily as influential as the whole scene taken together. I don’t think most people started with Deep Six, I think people started with whichever bands were actually putting out records that were from that. Skin Yard’s first record sold more copies than Deep Six ever made, the same was with Green River, The Melvins and obviously Soundgarden. Locally Soundgarden was one of the favorite bands of all of us, they were amazing, so when they finally came out with that first EP, literally everybody had it. I feel like that’s the point at which things were really starting to take form. Then there were more new bands. Nirvana first showed up around 1988, a couple of years after. There were bands like Feast, who actually never put a record, but locally they were huge favorites, you also had bands like Room Nine, for most people don’t even know, but in Seattle they were a big deal. I think Deep Six is very important piece of history because it’s essentially the official beginning of grunge, but most of that initial Seattle popularity happened when all of the bands together started putting out their own records. I guess some historians may disagree with me on that but when you look at the timeline you can see it. People that didn’t live in Seattle probably discovered Green River or Soundgarden or the Melvins or Skin Yard first, or maybe Nirvana first and then they started digging deeper and reading articles and thinking that “hey, something is going on with this record, it’s not in print anymore so I need to have a copy”.

If grunge had started with Deep Six, around that time, when do you think it would have ended? if ever, because maybe it hasn’t ended at all?

I don’t think it ever ended. There are new bands that keep coming out but draw from all of that, another movement, another genre. People like to put everything in a boxes, they like to call it something. Look for instance at stoner rock and all of the desert stoner rock scene. You have for example Kyuss and Kyuss ends up turning into Queens of the Stone Age in a matter of speaking. Grunge isn’t one thing. TAD, Skin Yard, Alice In Chains and Nirvana are all completely different bands but they’re shoved into a box as it they’re all the same. So, it’s kind of hard to say that grunge is one thing. You can say it’s heavy, intense, loud and dirty but it’s also melodic. Some of it is heavier than others, some of it is more complicated. You might say the Tool would not have ever come around if not for grunge. I don’t know, but I think Tool in certain ways started kind of coming from a place where Soundgarden were at the time. All Them Witches is another band I think probably would not be around without grunge. So, I don’t think it really ever ended, it just maybe goes by different names and it’s being created in new and different places.

Did the great boom for Seattle help the scene or, on the contrary, contribute to its downfall in some way, somehow destroy it?

Most of us who, lived there at the time, didn’t really like what was happening because suddenly it was turning into fashion. When we started out, it was intimate, everybody knew everybody else, we were going to the same parties, we were all sleeping with each other etc. And there was something very special about that intimacy. When everything exploded it suddenly became this whole other thing. Have you seen the movie Hype!?

Actually, it’s on my must-see list but I haven’t seen it yet.

There’s a scene in where Steve Fisk talks about the major labels. He compares them to this cartoon character named Baby Huey – this huge chicken with a diaper – who walks around, goes to a new scene, sits down on it and kills a few bands, then he gets up and goes over to the new scene, he sits down and kills a few more bands. And it was like that. Once money enters a scene, everything changes. Suddenly we’re not an organic music scene anymore, we are now a commodity, and everybody wants to basically make money off of it. So, after the major labels started signing all of these bands, suddenly all these new groups, not just in Seattle but all over America, were copying these bands. At C/Z we were suddenly receiving all of these demos that sounded like one of the many bands that were getting big at the time: Nirvana box there, Soundgarden box there etc. They didn’t interest us because they were just trying to do something that had already been done. It changed everything within our own scene because now also there were bands that nobody ever heard of, playing in the clubs in Seattle. We didn’t know who these people were, they just showed up out of nowhere. So, it helped a lot because, for instance, for me as a C/Z label record owner an explosion created interests in Seattle music around the world, so I could release new records by bands that nobody ever heard of and knew that at a minimum I could sell 5000 or 6000 copies simply because they were from Seattle. Just the word Seattle was all you needed to sell the records. This was in the early years of the 90’s, but after Kurt died, I couldn’t sell 5000 copies of a record anymore, the whole scene died after he died. The great boom helped all of us with the business part of music, it helped new bands that were from Seattle get a foot up, but it killed the organic quality of the scene and its intimacy, its spirit. We were now on the cover of every magazine in America, every newspaper, every news show on television wanted a piece of us. It started to leave a bad taste in our mouths.

I’ve read somewhere that Skin Yard is possibly the least appreciated of Seattle’s early grunge pioneers. Would you agree with that?

(Laughing) Well, of the Deep Six bands, I would probably tell us and maybe Malfunkshun. Soundgarden became huge, Pearl Jam and Mudhoney both came from Green River, Melvins are still together putting out records today and they’re amazing. The U-Men were already legendary. Malfunkshun never put out a proper record, although Andy did go on to be in Mother Love Bone. But I don’t think people talk about Malfunkshun a lot these days anymore. And Skin Yard at that time had the hardest time being recognized as part of that scene because a lot of what we’re doing musically was a little bit different, a little more complicated, we were kind of pushing the boundaries. We were also considered as a sister band of Soundgarden, not just because we shared a drummer—Matt Cameron—or played together a lot, but we we’re also the primary bands that were doing things a little more challenging. Time signatures and both bands liked doing things texturally. But eventually Skin Yard could headline on a Saturday and we could sell out any place in town. We were certainly not a band that ever got signed to a major label, but what’s interesting is that now there’s a lot of interest in Skin Yard and a lot of popularity, 30 years later. Maybe that’s the reason that I’m working on a Skin Yard oral history book.

Yes, I know that you are working on the book and I wanted to ask you about it. Well, I planned to do it in next few questions but as it came out, I’m going to ask it now – how is it going? When can we expect the book release?

Sometimes it’s going very well and sometimes it’s not. I’ve done over 60 interviews so far and I’m probably going to do another 10 to 20. Right now, my life is kind of in a lot of chaos because my wife and I are in the process of moving to a different city and we’re going to sell our house, so my focus is not on the book currently. But I’m going to finish putting it together. There’s a lot of stuff in there that people have never heard. I think a book about a band is usually more interesting than a book that attempts to cover a whole scene because you can get more specific. When you talk about a whole scene, you have to talk more broadly. I’m hoping to submit my proposal to publishers by the end of this year and I think I will. I won’t have the book finished by the end of 2021, but I’ll have some part of it done. I’m hoping I can have offers from publishers maybe by springtime of 2022 and then have it actually released by fall, this would be my ideal.

Do you have any other plans related to Skin Yard?

Actually, yes. We’re doing some Skin Yard work that people don’t know yet so you will be the first that can say something about it. Jack Endino and I have been working on a collection called “Skin Yard Select.” It’s just a collection of the songs that we think represent us the best from all of our different records. It’s not necessarily a greatest hits or anything like that, as we didn’t have any hits, and we’re not necessarily picking the most obvious songs. There’s also a couple of alternate versions of songs that people have never heard, there’s going to be at least one song that has never seen the light of a day. It’s from our very first record with Matt Cameron. It was just going to be digital only, but I think we’re actually going to do a limited-edition release, maybe just 1000 copies but a 7-inch box set, probably 8 different 45 rpm singles in a single set. We haven’t decided yet but probably we’re going to release it in a physical version first and then later, there’ll be a digital version.

That’s a great news! When do you plan to do it?

It depends on Jack’s schedule, we have to do all of the art design as well, which I’ll probably be overseeing. I’m going to work with an artist for all of the imagery and then I’ll probably work with Jeff Kleinsmith who is the art director for Sub Pop and an old friend of mine. I would like that to be done earlier next year. It’s going to be pretty cool. I think it will disappear very quickly, it’s not going to take three or four years to sell, rather three or four months, I guess.

Any chance for international shipping?

Yes, sure. But we need to find a distributor in Europe because sending them one at a time is going to be too difficult and too expensive. I’ll have to look for that. And then, we definitely won’t be the most underappreciated band on Deep Six. (laughing)

It’s interesting to note that although you were in charge of C/Z label, most of Skin Yard albums were released by Cruz Records. Why?

Because if you run the record label and you’re putting out your own records and you’re making money off the band, the other members of the band end up resenting you. You know, I’m putting out the records on my label and then as a label owner I’m getting paid and presumably also making money off the band and everybody in the band are like “fuck you.” Additionally, C/Z wasn’t as big, and I couldn’t do a lot of the things that a larger label could do for us. Cruz had the whole SST machine behind them, so they were able to actually pay for promotions, they were able to get the record out more effectively and I didn’t have to worry about that piece of the puzzle. And it was easier for the other members, that somebody else was making money. When you are in the band and somebody else is in your band with you, and he is putting out your records and he is actually making a profit off of you, then you feel like it’s an unfair balance of power.

Do you have your favorite C/Z record? Except Skin Yard obviously.

I have favorites, not one favorite. I put out 90 some odd records. Ok, let’s start from the earliest: I’m a huge fan of the first record by Vexed which is called The Good Fight. I just think it’s an amazing record by a band that virtually nobody knows. There’s the first record by Tone Dogs, Ankety Low Day, where Amy Denio played bass and sang. Matt Cameron played on that record too. I think one of the best records I’ve ever put out was Hammerbox. I love the first record by Treepeople. The second record by a group called My Name – Wet Hills and Big Wheels – is a pretty amazing record as well. I think that first The Gits record is absolutely fantastic, it’s a classic. I put out a Love Battery record called Confusion Au Go Go in 1999. Not many people have heard it, but I think it’s a great Love Battery album. Honestly, I’m proud of all the records I put out on C/Z. I never put out anything that I didn’t think was worth putting out but those mentioned are my favorites. At least right now, when you’re asking me!

C/Z does not put out records anymore. Have you ever considered coming back to business and running it again?

I don’t have any plans other than the Skin Yard singles box I told you about. I put out record that was just a collection of singles on C/Z that hadn’t come out anywhere else, just so there was sort of a collection. I also put out FEEdbACK album called Home Recordings 1984. FEEdbACK was an early band, pre–Skin Yard, that I played with Matt Cameron in. Those are the last two things I released. I don’t have any plans of putting stuff out, and if I do it’ll likely be digital only. It’s too much money and too much effort to try to put things out physically anymore. I did that and I’m done with that.

Let’s get back to the Skin Yard. The band took a 12-month hiatus right as the attention on Seattle reached its fever pitch. If there hadn’t been this break, the Skin Yard wouldn’t have fallen apart and would still be present on the stage, like for example Melvins?

You’re talking about the break between Fist Sized Chunks and 1000 Smiling Knuckles, correct?

Exactly.

Well, 1989 it was a hard year, for a lot of reasons. I had a son in March ‘89 so for me it was difficult to go on the road, but still, I went on and it was the worst tour in the world. We still refer to it as “the tour from Hell.” It was from April through May of 1989. Our van was breaking down constantly, we missed gigs, literally every problem you could have – we had. And last but not least, we had lot of difficulties within the band. Our drummer Scott was young, and he had a very hot head, he was a fiery drummer, and he was a fiery personality as well, and as a result there was a lot of tension in the band, internally. At one point, in the middle of the tour, Scott threatened to fly home if we didn’t give him more money. And the problem was we didn’t have any money. When we got back, we knew that we want to fire Scott because we couldn’t deal with him anymore. At the same time, during that tour, Scott and Ben, our vocalist, had started writing songs for what became later a Gruntruck. Jack and I did not know about it during that tour. When we fired Scott, they started doing the Gruntruck staff and Jack and I, we didn’t know if we had energy to keep doing it anymore. As it had been so difficult, we weren’t actually planning on being in a band again. Jack had just released a solo record under the name Endino’s Earthworm, and I’d done a record with Helios Creed called The Last Laugh on Amphetamine Reptile. So, we decided to take an indefinite break.

What caused the reunion?

Jack had an Earthworm gig with the Melvins in April 1990 and needed a bass player. I learned all the Earthworm stuff and we played the show. Barrett Martin was the drummer. We had a wonderful time – it was really fun! 2 months after that gig, we decided to make another run with Barrett as our drummer. We played our first Skin Yard show with Barrett in June 1990 and we went on a West Coast tour. I think the record we did with Barrett – 1000 Smiling Knuckles – was probably the best record we ever did. We had been around for 6 years at this point, we’re just finally starting to do well enough, that we could actually make a living off the band, but you know, there was still a lot of hard work to do and there was also still a lot of tension between me and Ben. Creatively Ben and I wanted to do different things, he wanted to be more like Gruntruck, and I wanted to stay a band that was still doing more adventurous music, pushing the boundaries. So, I decided just to leave the band in early 1991, about the same time that 1000 Smiling Knuckles came out. I think my last show was on February in 1991 and Skin Yard did their first show with the new bass player in April the same year. They played the last show that they ever played in Seattle in September and went on a fairly short U.S. tour, like 4 weeks. And I think they played their last show ever in the United States in October. Then they went to Europe for another 4 weeks and they played their last show ever in November 1991, 9 months after I left the band. When they came back, they recorded the songs that later became Inside the Eye.

The record that was released I guess about a year and a half after the band broke up.

You know, bands are like marriages, except for they are more complicated because it’s not between two people but between four or five people. When you have that many personalities, often very strong personalities, all trying to make things work, it’s pretty difficult. There’s a reason why most bands don’t last as even as long as Skin Yard. If you’re making a living and making a good living it’s easier to stay together because you don’t even have to be together, a band like Pearl Jam for instance – they’re not together all the time, right? Every couple of years they can get back together to work on a new record and tour and when they’re done, they can go their separate ways and be with their families. It makes it a lot easier, but I don’t think there’s anything that would have ever kept Skin Yard together for that long. I tried a few times to make something happen with Jack Endino and maybe with a different singer or maybe to have him as a singer and he just says “I don’t want to get back together in case we suck, because my lasting memories of how Skin Yard are left was all really good, we were at the top of our game in terms of how we were playing the songs, how we were writing. What if we got back together and try to play and if it was terrible? Then that would be my last memory”. And he is right, that’s a good reason. Nevertheless, Jack and I still talk regularly, we are close, so I wouldn’t be surprised if someday we’ll do something musical together again. I don’t think we would ever perform together again but I could see us doing some kind of recording project, that could happen.

I understand why you left the Skin Yard but why did you end up with music in general? Because you don’t play anymore, for so many years, right? Don’t you miss your bass guitar?

That’s true and it’s a good question. I played my first show after 27 years about two years ago with friends of mine from the San Francisco Bay area and it was so much fun. I was getting ready to start playing again with a couple of people out here in the desert and we were going to do another show but then COVID hit and that’s ended everything. But to answer your question, 1000 Smiling Knuckles was—to me—the closest I ever thought that I’d come to making my perfect record. It was hard for me to imagine ever being able to make a record that was as good as that one. Everything about it is fantastic. I think it contains the best songs we ever wrote. Jack and I – we have something very special working together, as a writing team. I had a hard time imagining I would ever be able to work with somebody again and have that same kind of chemistry, that same kind of magic. I felt like I had finally achieved what I had always wanted to do in that record, and I didn’t want to start with a new project just to feel disappointed. It took me probably 20 years to finally realize that it’s ok to do something, maybe not as good, because I think at this point if I’ll do something new, it will be different enough that it won’t matter anymore. And I have been thinking a lot trying to play music again, but I don’t know if it will be a band. I think it might be a “project.” As much as it’s fun to play out, I have to admit I don’t like touring (laughing). I’m also a lot older than I was when I left Skin Yard. I was not yet 30 years when I played my last show with Skin Yard and this coming summer I’m about to be turning 60. HALF of my life ago! That’s nuts. Touring is no fun when you are old, I’m pretty sure, but we’ll see. I still have my bass.

O procesie powstawania i znaczeniu legendarnej już dziś kompilacji Deep Six, zespole Skin Yard i związanych z nim planach, wytwórni C/Z Records, a także o muzycznej scenie Seattle, wielkim boomie na grunge i tym, co z niego zostało, opowiada Daniel House – basista i współzałożyciel wspomnianej wyżej grupy oraz wieloletni właściciel i szef niezależnej wytwórni C/Z, której logo sygnowało płyty takich zespołów, jak między innymi: 7 Year Bitch, The Gits, Hammerbox, Love Battery, The Melvins czy The Presidents of the United States of America.

Kompilacja Deep Six jest dziś już wydawnictwem legendarnym dla muzycznej sceny Seattle, to jedna z pierwszych i jedna z najważniejszych płyt w historii grunge’u. 21 marca obchodziła swoje 35-lecie…

To już 35 lat? Wow, nie do wiary. Wiem, że jest to ważna pozycja z historycznego punktu widzenia, ale dla każdego z nas, kto tam był, cóż… nikt z nas tak naprawdę nie myślał, że robimy coś wielkiego. To była bardzo mała scena w tamtym czasie, nie było zbyt wielu zespołów, nie było zbyt wielu klubów, publiczność stanowili nasi znajomi i przyjaciele, wszyscy chodziliśmy nawzajem na swoje koncerty. Mieliśmy jeszcze po naście lub niewiele ponad 20 lat więc po prostu graliśmy i dobrze się bawiliśmy. Na płycie znalazły się tylko 2 zespoły, które miały już wcześniej jakiekolwiek nagrania na swoim koncie: Green River i U-Men.

Patrząc z takiej perspektywy czasu – trzy i pół dekady później – jak oceniasz ten album? Z obu punktów widzenia – muzyka, który uczestniczył w projekcie i człowieka, który został później właścicielem C/Z Records – wytwórni, która wydała ten krążek?

Z jednej strony Deep Six jest pierwszą płytą, która zaznaczyła na muzycznej scenie początek czegoś zupełnie nowego, czegoś, co zaczynało się kształtować, ale jak wspomniałem, nikt z nas do tego nie dążył, to się po prostu wydarzyło. Zakładam, że wiesz, że to nie ja jestem osobą, która wydała ten album.

Tak, za pomysłem i realizacją stali Chris Hanzsek i Tina Casale.

Dokładnie. Tyle że, gdy płyta wyszła niewiele osób ją kupiło. Nakład stanowiło 2000 sztuk, z czego myślę, że każdy z poszczególnych zespołów dostał trzy lub cztery egzemplarze. W Seattle może kolejnych 200 sztuk zostało sprzedanych i w zasadzie to by było na tyle. Ludzie poza miastem nie znali żadnego z tych zespołów więc po prostu nie byli zainteresowani tym krążkiem. Chris otworzył również w tym czasie studio i pamiętam, że miał całe pudła tych albumów poupychane pod łóżkiem. Nikt ich nie kupował, było może ich 5 lub 10 na raz w sklepach z płytami. Wydał dużo pieniędzy na zrealizowanie i wypuszczenie nagrań i dość szybko zdał sobie sprawę, że prowadzenie wytwórni zwyczajnie mu się już nie opłaca. To były początki Skin Yard i ja sam w tym czasie byłem bardzo zainteresowany nagrywaniem oraz wydawaniem muzyki. Podczas Gdy Chris nie miał już w tym żadnego interesu, ja miałem go coraz więcej, więc kupiłem od niego wytwórnię, razem ze wszystkimi zapasami i płytami i zacząłem pracować nad ich dystrybucją. Myślę, że zajęło mi to 3 lub 4 lata, aby w końcu sprzedać większość tych albumów. Pomimo, że zostało jedynie mniej więcej 700 – 800 sztuk, zajęło to tak dużo czasu. Teraz mam jeszcze około 10 – 12 egzemplarzy i mogę je sprzedać po 350,00 dolarów za sztukę. Teraz każdy chce tę płytę mieć. Tak więc z biznesowego punktu widzenia Deep Six odniósł sukces, ale dopiero wiele, wiele lat później. Z muzycznego punktu widzenia natomiast, cóż… przede wszystkim uważam, że jest to bardzo ważny dokument. Z jednym wyjątkiem – mojego własnego zespołu. Skin Yard był prawdopodobnie najmłodszą grupą na tej kompilacji, ledwo co się zawiązaliśmy i myślę, że wciąż zastanawialiśmy się, kim byliśmy jako zespół. Nasze kawałki na Deep Six to jedyne nagrania Skin Yard, które sprawiają, że czuję zażenowanie kiedy ich słucham. Z jednej strony bardzo się cieszę, że jesteśmy na tej płycie, ponieważ myślę, że gdyby nas tam nie było, historia mogłaby zapisać naszą muzykę na swych kartach w zupełnie innym miejscu, moglibyśmy nie zostać uznani za ważnych dla tej sceny. Z drugiej strony, chciałbym, aby nikt nie mógł usłyszeć tych kawałków, bo myślę, że są po prostu straszne.

Ja nie uważam, aby były straszne.

To miłe, ale nic nie poradzę, sądzę, że jednak są. Nie wydaje mi się, aby wiele osób tak myślało, ale wiesz, w tamtym momencie nasz wokalista nie za bardzo jeszcze wiedział jak śpiewać. Z perspektywy czasu myślę, że są na tej płycie 2 zespoły, których obecność nie ma większego sensu i które za bardzo tu nie pasują: to jesteśmy my i jest to również U-Men. The U-Men byli bardzo charakterystyczni i po części to jest powód, dla którego byli tak popularni. W Seattle nie było nikogo, kto brzmiałby podobnie do nich. Jedyne zespoły, które w jakimś stopniu można do nich porównać to może The Birthday Party i może w jakimś niewielkim stopniu The Gun Club.

Patrząc wstecz, z wiedzą i doświadczeniem, które posiadasz dziś, poprowadziłbyś inaczej promocję Deep Six?

Prawdopodobnie niczego bym nie zmienił. Gdy Deep Six się ukazało było jedynie dokumentem małej, malutkiej wręcz sceny w mieście, które nikogo nie obchodziło do czasu, gdy niektóre zespoły zaczęły podpisywać kontrakty z wielkimi wytwórniami. Raczej zastanowiłbym się nad tym jak wyglądał świat muzyki przed globalnym dostępem do sieci internetowej i w jakim stopniu ta sieć wszystko zmieniła. Przed rewolucją internetową istniało wiele scen regionalnych zarówno w USA, jak i najpewniej w Europie, które rozwijały się bardzo organicznie. Takie rzeczy są możliwe we względnej izolacji. W Stanach mieliśmy scenę Seattle, ale mieliśmy też scenę w Nowym Jorku, z zespołami takimi jak Live Skull czy Sonic Youth, która była totalnie inna. Wiele osób nazywa tę scenę “No Wave”, ale to był pewien rodzaj noise rocka. Była również scena w Minneapolis, była scena DC z wytwórnią Dischord i zespołami takimi jak Minor Threat, była w końcu też scena w Atenach, w stanie Georgia, która również była zupełnie odmienna. I wiele, wiele innych.

I wtedy pojawił się Internet…

I nagle wszyscy mogli usłyszeć co robią inni, gdziekolwiek w świecie, więc nagle wszyscy mogli czerpać wpływy zewsząd i to w czasie realnym. Nie wiem co dzieje się muzycznie w Polsce, ale jeśli chciałbym sprawdzić, prawdopodobnie jestem w stanie całkiem szybko się zorientować. Z jednej strony to jest super, ale z drugiej zabija to możliwość rozwoju regionalnych scen w sposób organiczny. I dla mnie jest to w jakimś sensie rozczarowujące. Internet ułatwia promowanie muzyki, ale sceny artystyczne nie mogą się już rozwijać naturalnie… więc każdy kij ma dwa końce. Myślę, że scena Seattle okazała się ostatnią tego typu organiczną sceną. Dotarcie z Deep Six na poziom ogólnokrajowy zajęło tyle czasu, ile zajęło, ponieważ nie było Internetu. To był bardzo powolny proces. A w międzyczasie, zespoły znajdujące się na kompilacji, zaczęły wydawać coraz więcej swojej muzyki. W Skin Yard nagrywaliśmy kolejne materiały, Soundgarden nagrywał i wydawał następne rzeczy i to właśnie Soundgarden był oczywiście częściowo powodem tego, że ta scena w ogóle wybuchła i stała się tak wielką. U-Men wydali kolejne płyty. Malfunkshun był jedynym zespołem z kompilacji, który rozpadł się dość szybko, ale potem na jego fundamentach powstał Mother Love Bone. I gdy ludzie odkryli Mother Love Bone, ponownie pod wielką wytwórnią, zaczęli grzebać w przeszłości zespołu, aby dowiedzieć się skąd się wziął, kim byli jego członkowie wcześniej. I wtedy trafiali na Deep Six.

W tamtym czasie sprzedaż Deep Six osiągnęła względnie zadowalający poziom w Seattle i okolicach, ale w perspektywie ogólnokrajowej wyniki były raczej rozczarowujące. Dziś jest to jeden z najbardziej pożądanych albumów wśród fanów brzmienia Seattle nie tylko w Stanach, ale na całym świecie. W 1994 roku miała miejsce re-edycja albumu, ale w dalszym ciągu zdobycie go jest niemal niemożliwe. Czy przy takim popycie jest Twoim zdaniem szansa na kolejną re-edycję płyty, przykładowo na jej 40-lecie?

Nie wydaje mi się. Powodem, dla którego A&M Records zdecydowało się na re-edycję albumu w 1994 roku był fakt, że znajdował się na nim Soundgarden, który w tym czasie był związany z A&M kontraktem. Wytwórnia chciała przede wszystkim zabezpieczyć możliwie jak najwięcej nagrań zespołu żeby móc w pełni je kontrolować. Nie interesowały ich pozostałe grupy. W tamtym czasie, gdy jeszcze Deep Six należało do C/Z Records, Susan Silver powiedziała mi mniej więcej coś takiego: “chcą kupić tę płytę od Ciebie za w miarę przyzwoite pieniądze, jeśli się nie zgodzisz zabiorą ją i tak i zostaniesz z niczym”. W A&M był dział prawny i z ich perspektywy wyglądało to mniej więcej tak: “Twój kontrakt nie jest dobrze skonstruowany, możemy więc to zabrać i niewiele możesz na to poradzić”. Susan wiedziała, że to byłoby nie w porządku, znalazła więc pewne rozwiązanie. Ostatecznie dostaliśmy jakieś pieniądze oraz zapis w kontrakcie, że A&M wyda płytę na CD (jako, że nigdy wcześniej na CD wydana nie była). Z zapisu się wywiązali, ale nieszczególnie zależało im na promocji tego krążka. Nie sądzę nawet, aby dziś większość ludzi w A&M wiedziała czym Deep Six w ogóle jest. Nie sądzę również, aby mogli zrobić re-edycję bez zgody każdego ze znajdujących się na płycie zespołów. To z kolei zapewne sporo by kosztowało więc tym bardziej im na tym nie zależy. To nie jest sposób w jaki działają majorsi. Ja natomiast nie mogę zrobić re-edycji ponieważ sprzedałem prawa do tego albumu.

Jak wspominasz proces powstawania Deep Six i dwu-wieczorowy koncert z okazji wydania albumu w UTC Hall (Seattle) 21 i 22 marca 1986 roku?

Wydaje mi się, że to ja byłem tym, który namówił Chrisa na ściągnięcie U-Men na płytę. Oni nie chcieli na niej być. Powiedziałem mu: “są aktualnie największym lokalnym zespołem i po prostu musisz ich mieć, jeśli nie będziesz ich miał trudno będzie Ci sprzedać te płyty.” Cóż, problemy ze sprzedażą były i tak, ale bez U-Men na płycie byłoby z pewnością jeszcze gorzej. Każdy z zespołów spędził 2 dni w studio i tylko jedna osoba z grupy mogła być obecna przy miksowaniu materiału. Ze Skin Yard był to Jack Endino, który był już naszym inżynierem dźwięku więc miało to sens, z Green River wydaje mi się, że był to Jeff Ament, z Melvins prawdopodobnie Buzz Osborne; nie jestem pewien jeśli chodzi o Soundgarden czy był to Chris (Cornell, przyp.red.) czy Kim (Thayil, przyp.red.). Odnośnie koncertu mam nieco wyblakłe wspomnienia, bo było to bardzo dawno temu, ale wiem, że byłem zaangażowany w przygotowania i że zaprojektowałem plakat. W pewnym sensie współpromowałem ten koncert z kimś, ale nie pamiętam kto to był. Może Ty wiesz, z researchu?

Niestety, szukałam tej informacji, ale nie znalazłam odpowiedzi.

Kurcze, serio nie pamiętam. No mniejsza z tym. Wracając do sedna, sześć zespołów to za dużo jak na jeden wieczór, dlatego podzieliliśmy koncert na dwa dni. Właściwie to nie był tylko koncert, ale cały event. Mieliśmy limitowaną liczbę biletów na obie noce, dodatkowo każdy z zespołów miał limitowaną ilość osób, które mógł wpisać na listę gości. Drugą noc otwierało Malfunkshun, potem na scenie pojawiliśmy się my a na koniec U-Men jako headliner. Pierwsza noc natomiast, jeśli mnie pamięć nie myli, to najpierw Soundgarden, potem Melvins i na koniec Green River.

Według plakatu dokładnie taka kolejność była w dniu Skin Yard, pierwszej nocy było to natomiast Melvins, potem Soundgarden i Green River jako headliner.

A tak, faktycznie. Obie noce były wyprzedane, bilety rozeszły się całkiem szybko. Większość ludzi była obecna na obu koncertach. Gigi były bardzo intensywne, głośne i totalnie ekscytujące, dało się wyczuć, że “coś się dzieje, coś wisi w powietrzu”. Myślę, że koncerty te scementowały występujące grupy jako tzw. pionierów sceny. Byliśmy zespołami reprezentującymi tę nową niszę, która zaczynała się coraz śmielej kształtować. Jak już podkreślałem, nikt do tego nie dążył, to się po prostu wydarzyło, organicznie. Wcześniej przeważał tu może taki bardziej art rock, trochę new wave, może trochę rockabilly, a nagle pojawiły się zespoły, które zaczęły grać mocniej, ciężej, głośniej i bardziej brudno.

John Peel z londyńskiego The Times nazwał brzmienie Seattle “najbardziej charakterystycznym amerykańskim brzmieniem od czasów Tamla Motown”. Skąd, Twoim zdaniem, wziął się ten brudny, ciężki styl? Jakie jest tło dla powstania tego charakterystycznego gatunku?

To wspaniały komplement, ale myślę, że większość z nas nie zgodziłaby się z tym stwierdzeniem. Wszyscy czerpaliśmy mniej więcej z tych samych wpływów, z zespołów, które były już przecież przed nami. Cała scena czerpała inspiracje z hard rocka, arena rocka i undergroundowych, mało znanych rzeczy. Z arena rocka możemy znaleźć sporo nawiązań do Black Sabbath na przykład. W Green River możemy zauważyć wpływ Aerosmith – zdecydowanie inspirowali się The Stooges, ale również grupą Stevena Tylera. Zespoły takie jak Soundgarden czy Melvins, były pod wpływem pewnie bardziej Black Sabbath, ale też undergroundowych zespołów, które z kolei brały sporo z hard rocka. W tamtym momencie Skin Yard czerpało więcej z takich zespołów, jak King Crimson. U-Men byli pewnie pod wpływem The Birthday Party i tym podobnych grup. Ale, generalnie, wszyscy byliśmy zainspirowani zespołami, które były już na scenie. Wszyscy słuchaliśmy też podobnej muzyki. Wielu z nas dorastając w liceach słuchało wczesnego AC/DC, Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, Aerosmith, ale też The Stooges czy MC5. Było również sporo mało znanych zespołów, którymi inspirowało się wiele osób, zwłaszcza tych które kopały głębiej – w muzyce wczesnych lat 70 czy późnych 60 – więc jest też sporo wpływów z garażowego rocka pokroju The Sonics czy The Wailers. Do tego doszło jeszcze później trochę psychodelii, która wywodziła się z okolic Detroit. Mamy wpływy nawet zespołów takich jak – nie mogę go znieść jako istoty ludzkiej, uważam, że jest okropnym człowiekiem, ale jego pierwsze nagrania są świetne – Ted Nugent and The Amboy Dukes. Byliśmy pod wpływem tego, czego słuchaliśmy, a było to też mniej więcej w czasie wczesnych Sonic Youth i Bad Brains, tak więc ich śladów pewnie można się gdzieś też doszukać. Byliśmy jak gąbki, chłonęliśmy wszystko, przeżuwaliśmy, reinterpretowaliśmy i przeobrażaliśmy na swój sposób. Ale myślę, że dużo podobnych wpływów możemy usłyszeć też na innych rockowych scenach, jak np. w Minneapolis I w zespołach takich jak The Replacements. Chociaż oni może byli bardziej pod wpływem punka, a my bardziej pod wpływem jeszcze cięższych rzeczy.

A na Ciebie, które zespoły wpłynęły najmocniej?

Było ich tak wiele, ale niech pomyślę… Żeby wymienić tylko kilka, sądzę, że w tamtym czasie byłem bardziej pod wpływem Led Zeppelin niż Black Sabbath. Był też taki brytyjski zespół, którego większość ludzi w USA w ogóle nie zna, a który wpłynął szczególnie na Jacka Endino i później na mnie – The Groundhogs. I jeszcze jedna grupa z Londynu – King Crimson. Poniekąd nawet Bauhaus. Seattle w tamtym okresie było ponure i niebezpieczne więc myślę, że miasto samo w sobie także wywarło jakiś wpływ na moją twórczość. Jako grupa czerpaliśmy też poniekąd z Killing Joke i The Stooges. Właściwie myślę, że to zespoły z Seattle spowodowały wzrost zainteresowania pierwszymi nagraniami grupy Iggy’ego Popa, w tej chwili ich pozycja jest znacznie mocniejsza niż wtedy, gdy pojawili się na scenie. Wówczas nikt zbytnio się nimi nie interesował ponieważ byli zbyt skandaliczni, zbyt oburzający. A teraz? Teraz ludzie patrzą na The Stooges, na ich pierwsze nagrania i nadają im status kultowych, traktują ich jak bogów. I właściwie tak, oni byli w pewnym sensie bogami.

Jak oceniłbyś wpływ Deep Six na muzyczną scenę regionu PNW? (Pacific North-West – przyp.red.)

Nie sądzę, aby ten album sam w sobie miał aż tak duży wpływ, jak wszystkie zespoły razem wzięte. Nie wydaje mi się, aby większość ludzi zaczynała od tej płyty, raczej zaczynali od którejkolwiek z obecnych na niej grup. Pierwsza płyta Skin Yard sprzedała się w większym nakładzie niż całe Deep Six, tak samo płyty Green River, Melvins oraz oczywiście Soundgarden. Lokalnie Soundgarden było jednym z ulubionych zespołów nas wszystkich, byli wprost niesamowici, więc gdy w końcu wyszła ich pierwsza EP-ka, miał ją dosłownie każdy. Myślę, że to jest moment, od którego to wszystko zaczęło się dziać. Potem pojawiło się jeszcze więcej nowych zespołów. Nirvana ukształtowała się w 1988 roku, kilka lat później. Był taki zespół Feast, który właściwie nigdy nie wydał płyty, ale lokalnie był jednym z wielkich faworytów. Podobnie Room Nine – w skali krajowej prawie nieznany, ale na regionalnej scenie niezwykle ważny. Deep Six jest istotne bo to od tego krążka tak naprawdę oficjalnie zaczyna się historia grunge’u, ale cała ta popularność Seattle zaczęła się dopiero w momencie, kiedy zespoły zaczęły wydawać własne materiały. Część historyków muzyki pewnie się ze mną nie zgodzi, ale jak popatrzysz na oś czasu, to widać to dość wyraźnie. Ludzie, którzy nie mieszkali w Seattle najpewniej najpierw odkryli Green River, Soundgarden, Melvins albo Skin Yard, a może nawet na początek Nirvanę i dopiero wtedy zaczynali kopać głębiej. Wówczas trafiali na artykuły o Deep Six i działało to na zasadzie: “hej, coś jest na rzeczy z tą płytą, nie jest już dostępna więc muszę ją mieć”.

Jeśli grunge zaczął się w okresie Deep Six, to kiedy – Twoim zdaniem – mniej więcej się skończył? Jeśli kiedykolwiek, bo może nie skończył się wcale?

Nie sądzę, aby kiedykolwiek się skończył. Jest wiele nowych zespołów, które czerpią z tego brzmienia, tyle, że jest to nowy ruch, nowy gatunek. Popatrzmy na przykład na stoner rock i cały ten desert stoner rock, na Kyuss, który częściowo przekształcił się później w Queens of the Stone Age. Natura ludzka ma to do siebie, że lubi układać wszystko w odpowiednio ponazywanych szufladkach. Tymczasem grunge jest bardzo złożony. TAD, Skin Yard, Alice In Chains i Nirvana to kompletnie różne zespoły, które zostały włożone do jednej przegródki. Niektóre są bardziej ciężkie, inne nieco bardziej skomplikowane. Trudno więc powiedzieć, że grunge to jeden styl. Możemy oczywiście określić, że jest ciężki, intensywny, głośny oraz brudny, ale jest też melodyjny. Możemy zaryzykować stwierdzenie, że nie byłoby zespołu Tool gdyby nie grunge. Nie wiem tego na pewno, ale wydaje mi się, że w pewnym sensie Tool pochodzi z tego samego muzycznego miejsca, w którym znajdował się Soundgarden. Kolejnym takim zespołem, prawdopodobnie, jest All Them Witches – ich również być może by nie było, gdyby nie brzmienie Seattle. Więc tak naprawdę moim zdaniem grunge się nie skończył, może jedynie jest teraz inaczej nazywany, tworzy się go nieco inaczej i w zupełnie innych miejscach.

Wielki boom na Seattle pomógł scenie czy przeciwnie – poniekąd przyczynił się do jej upadku, wpłynął na nią destrukcyjnie?

Większości z nas, która mieszkała wtedy w Seattle, nie podobało się to, co zaczęło się dziać, ponieważ nagle to wszystko zaczęło się zmieniać w modę. Kiedy zaczynaliśmy, to była to mała, intymna scena, wszyscy się znali, chodziliśmy na te same imprezy, spotykaliśmy się w tym samym gronie. I było coś wyjątkowego w tej intymności. Kiedy wszystko wybuchło nagle to zupełnie się przeobraziło. Widziałaś film Hype! ?

Jest od dawna na mojej liście must-see, ale jeszcze nie miałam okazji go obejrzeć.

Jest tam taka scena, gdzie Steve Fisk opowiada o wielkich wytwórniach. Porównuje je do kreskówkowej postaci Baby Huey’a – tego wielkiego kurczaka z pieluchą – który chodzi w kółko, wchodzi na nową scenę, siada na niej i zabija kilka zespołów. Wstaje, idzie dalej, znowu nowa scena i znowu ten sam scenariusz. I tak to mniej więcej wyglądało. Kiedy wkraczają pieniądze, wszystko się zmienia. Już nie jesteśmy organiczną, naturalną sceną muzyczną tylko stajemy się towarem, na którym wszyscy dookoła chcą zarobić. Kiedy wielkie wytwórnie zaczęły podpisywać kontrakty z lokalnymi zespołami nagle wszystkie nowe grupy, nie tylko z Seattle, zaczęły kopiować te zespoły. W naszej wytwórni C/Z Records dostawaliśmy całe stosy demo, które brzmiały dokładnie tak jak bandy, które stawały się wielkie. Odkładaliśmy je tylko na kupki: demo w stylu Soundgarden tu, demo w stylu Nirvany tam itd. Nie byliśmy oczywiście tym zainteresowani, bo po prostu oni wszyscy próbowali zrobić to, co zostało już zrobione. Boom zmienił też dużo wewnątrz naszej sceny. Nagle pojawiły się zespoły, o których nikt nigdy wcześniej nie słyszał, pojawiło się pełno grup znikąd, ludzi, których nikt nie zna, grających w klubach Seattle. Poniekąd to wielkie zainteresowanie pomogło, bo na przykład jako właścicielowi C/Z było mi dużo łatwiej sprzedawać płyty. Mogłem w ciemno wydać album zespołu, o którym nikt wcześniej nie słyszał i mieć pewność, że rozejdzie się minimum 5-6 tysięcy kopii tylko dlatego, że grupa jest z Seattle. To było to jedno magiczne słowo, które wystarczało do tego, żeby sprzedawać płyty. Tak było na początku lat 90., ale po śmierci Kurta (Cobaina, przyp.red.) nie byłem w stanie sprzedać już takiej ilości albumów. Razem z nim umarła cała scena, po wielkim boomie został wielki pył. Wielki boom pomógł więc naszemu środowisku od strony biznesowej, pomógł też zaistnieć kilku zespołom, ale zabił naturalność, intymność i ducha tej sceny. Byliśmy nagle na okładkach magazynów w całych Stanach, we wszystkich gazetach, każda telewizja chciała nas mieć u siebie. I to zaczęło gorzko smakować.

Przeczytałam gdzieś, że Skin Yard jest prawdopodobnie najmniej docenianą grupą spośród pionierów wczesnej sceny grunge. Zgodziłbyś się z tym stwierdzeniem?

(Śmiech). Cóż, jeśli chodzi o Deep Six to powiedziałbym, że my i pewnie Malfunkshun. Soundgarden stał się wielki, Pearl Jam i Mudhoney wywodzą się z Green River, Melvins wciąż grają, wydają płyty i są niesamowici. U-Men już wtedy był legendą. Malfunkshun nie wydał żadnego albumu, ale Andy (Wood, przyp. red.) stworzył Mother Love Bone. Myślę jednak, że niewiele osób pamięta dziś o Malfunkshun. Co do Skin Yard natomiast, to w tamtym czasie nie byliśmy do końca utożsamiani z tą sceną ponieważ to, co robiliśmy muzycznie, było nieco inne, trochę bardziej skomplikowane, przekraczaliśmy pewne granice. Często byliśmy określani jako siostrzany zespół Soundgarden, nie tylko ze względu na współdzielenie perkusisty – Matta Camerona, nie dlatego też, że często razem graliśmy, ale przede wszystkim ponieważ obie nasze grupy były pierwszymi zespołami, które robiły muzykę nieco inaczej. Jak pokazuje czas, obie nasze grupy lubiły robić rzeczy teksturalnie. Ale, ostatecznie, Skin Yard mógł być headlinerem na sobotnim koncercie i bez problemu wyprzedać każde miejsce w mieście. Oczywiście jednocześnie jesteśmy też zespołem, który nie podpisał nigdy kontraktu z wielką wytwórnią. I to pewnie też ma poniekąd wpływ na taką a nie inną ocenę. Ale, co ciekawe, teraz Skin Yard jest bardziej popularne niż te 30 lat temu, odnotowujemy znaczny wzrost zainteresowania naszą grupą. Może to jest też powód, dla którego pracuję nad książką, która będzie opowiadaną historią zespołu.

Wiem, że pracujesz nad tą książką i miałam o to zapytać nieco później, ale skoro pojawił nam się ten temat zapytam już teraz – jak postępują prace? Kiedy mniej więcej możemy spodziewać się publikacji?

Czasem idzie bardzo dobrze, czasem gorzej. Przeprowadziłem jak dotąd ponad 60 wywiadów i pewnie zrobię jeszcze 10 do 20. Aktualnie żyję trochę w chaosie, ponieważ razem z żoną jesteśmy w trakcie sprzedaży domu i przeprowadzki do innego miasta, więc chwilowo moja uwaga skupia się na innych rzeczach. Ale planuję to złożyć w całość. Jest tam dużo materiałów, których ludzie nigdy nie słyszeli. Książki o zespołach są zawsze moim zdaniem ciekawsze niż książki o całej scenie, bo można wejść w temat bardziej szczegółowo. Kiedy mówisz o całej scenie, mówisz szeroko, w przypadku biografii grupy zagłębiasz się dokładnie w jej historię. Mam nadzieję złożyć oferty wydawnicze do końca tego roku. Myślę, że to się wydarzy. Nie skończę do tego czasu książki, ale jej część na pewno będzie już gotowa. Idealnie byłoby otrzymać odpowiedzi od wydawców wiosną przyszłego roku i wówczas wydać książkę jesienią 2022.

Masz jeszcze jakieś plany związane ze Skin Yard?

Właściwie tak. Planujemy coś, o czym jeszcze nikt nie wie, więc będziesz pierwszą osobą, która może cokolwiek o tym wspomnieć. Razem z Jackiem Endino pracujemy nad kolekcją Skin Yard Select. Będzie to przekrojowy zbiór utworów, które najlepiej nas reprezentują, idealnie oddają charakter zespołu. Niekoniecznie będzie to wydawnictwo w stylu “greatest hits”, bo my nie mieliśmy nawet żadnych hitów, ale nie będzie to też zbiór najbardziej oczywistych kawałków. Dodatkowo pojawi się kilka alternatywnych wersji utworów, których nikt nigdy nie słyszał i przynajmniej jeden kawałek, który nigdy nie ujrzał światła dziennego. To coś z naszych pierwszych nagrań z Mattem Cameronem. Początkowo planowaliśmy wydawnictwo tylko cyfrowe, ale ostatecznie planujemy też fizyczną edycję limitowaną. Będzie to może około 1000 kopii, vinylowych box setów, składających się pewnie z 8 różnych 45-ek. Jeszcze nie zdecydowaliśmy ostatecznie, ale najpewniej najpierw wypuścimy wersję fizyczną, a dopiero potem digitalową.

Świetna wiadomość! Kiedy planujecie to zrobić?

Wszystko zależy od kalendarza Jacka, musimy zająć się też jeszcze oprawą graficzną, którą najpewniej wezmę na siebie ja. Zamierzam stworzyć wspólnie z artystą całą warstwę obrazową i wtedy rozpocznę prace nad realizacją projektu wspólnie z Jeffem Kleinsmithem, który jest dyrektorem artystycznym Sub Popu i jednocześnie moim starym, dobrym znajomym. Chciałbym, aby całość była gotowa na początku przyszłego roku. Myślę, że wyjdzie to wszystko całkiem fajnie i że nakład szybko się rozejdzie. Zakładam, że sprzedaż nie zajmie trzech czy czterech lat, a bardziej trzy/cztery miesiące.

Bierzecie pod uwagę dystrybucję międzynarodową?

Jasne, ale musimy najpierw znaleźć dystrybutora w Europie ponieważ wysyłka pojedynczych sztuk byłaby zbyt problematyczna i zbyt droga. Muszę się tym zająć. A gdy to się uda, wtedy zdecydowanie nie będziemy już najbardziej niedocenianym zespołem Deep Six (śmiech).

Warto podkreślić, że chociaż byłeś właścicielem C/Z Records większość albumów Skin Yard została wydana przez Cruz Records. Dlaczego?

Jeśli prowadzisz wytwórnię, w której wydajesz własne rzeczy i dodatkowo zarabiasz na tym, pozostali członkowie bandu oburzają się. Wiesz, wydaję nasze płyty w swojej wytwórni i jako właściciel labelu zarabiam na zespole, więc wszyscy w grupie przyjmują postawę: “fuck you”. Poza tym, C/Z nie było aż tak duże i nie mógłbym zrealizować z zespołem wielu rzeczy, które mogliśmy zrobić pod skrzydłami większej wytwórni. Cruz mieli całą machinę SST za sobą więc byli w stanie płacić za promocję, lepiej ją prowadzić, skuteczniej sprzedawać płyty. Ja więc nie musiałem się martwić o te aspekty, a dla grupy łatwiejsze do zniesienia było to, że zarabia na tym wszystkim ktoś trzeci. Kiedy jesteście razem w zespole i jedna osoba ma wydawać wasz materiał i tym samym zarabiać na tobie wtedy czujesz, że jest tu jakiś niesprawiedliwy rozkład sił.

Masz swoja ulubioną płytę, którą wydałeś w C/Z? Poza Skin Yard oczywiście. (Pod szyldem C/Z Records ukazała się pierwsza płyta zespołu, wydana w 1986 roku oraz wypuszczona w 2001 roku kompilacja Start At The Top – przyp.red.)

Mam kilka ulubionych, nie jedną. Wydałem ponad 90 różnych płyt, więc trudno byłoby się zdecydować na pojedynczy materiał. Zaczynając od najwcześniejszych: jestem wielkim fanem pierwszej płyty Vexed – The Good Fight. Myślę, że to wspaniały album zespołu, którego nikt nie zna. Dalej była pierwsza płyta Tone Dogs – Ankety Low Day – gdzie na basie i wokalu jest Amy Denio. Matt Cameron też tam gra. Myślę, że jednym z najlepszych albumów, jakie kiedykolwiek wypuściłem, jest Hammerbox. Uwielbiam pierwszą płytę Treepeople. Drugi krążek grupy My Name – Wet Hills and Big Wheels – jest również świetny. Pierwszy album The Gits jest absolutnie fantastyczny, to już klasyka. Wydałem też płytę Love Battery zatytułowaną Confusion Au Go Go w 1999 roku. Niewiele osób ją słyszało, ale uważam, że to genialny album. Zupełnie szczerze jestem dumny ze wszystkich płyt, które wypuściłem w C/Z Records. Nigdy nie wydałem niczego, o czym nie byłbym przekonany, że jest warte wydania. Ale te, które wymieniłem, to chyba moje ulubione płyty. No, przynajmniej na ten moment, kiedy mnie o to pytasz.

C/Z nie wydaje już albumów. Rozważałeś kiedykolwiek powrót do biznesu?

Nie mam żadnych planów poza zestawem Skin Yard Select, o którym wspomniałem. Jakiś czas temu wypuściłem też kolekcję singli, które nie były wydane nigdzie indziej oraz album FEEdbACK – Home Recordings 1984. FEEdbACK był pierwszym zespołem, jeszcze przed Skin Yard, w którym grałem z Mattem Cameronem. To są ostatnie 2 rzeczy, jakie wypuściłem. Nie planuję kolejnych, a jeśli przyszłoby mi coś do głowy, to byłby to raczej i tak wyłącznie digital. Wydawanie płyt w wersjach fizycznych kosztuje już dziś zarówno za dużo wysiłku, jak i za dużo pieniędzy. Robiłem to i już z tym skończyłem.

Wróćmy do Skin Yard. Zespół zrobił sobie roczną przerwę na moment przed tym, gdy gorączka Seattle osiągnęła swój punkt szczytowy. Czy gdyby nie ta przerwa zespół nie rozpadłby się i byłby obecny na scenie po dziś dzień, jak przykładowo Melvins?

Masz na myśli przerwę pomiędzy Fist Sized Chunks i 1000 Smiling Knuckles, zgadza się?

Dokładnie.

Cóż, 1989 to był trudny rok, z wielu powodów. W marcu ‘89 urodził mi się syn, więc trudno było mi wyruszyć w trasę, ale nadal, mimo wszystko, pojechałem. I była to najgorsza trasa na świecie. Po dziś dzień nazywamy ją “trasą z piekła”. Trwała mniej więcej od kwietnia do połowy maja. Nasz van nieustająco się psuł, przepadały nam koncerty, dosłownie – każdy problem, jaki tylko mógł pojawić się w trasie, pojawiał się. Co więcej, mieliśmy sporo problemów wewnątrz zespołu. Nasz perkusista Scott (McCullum – przyp.red.) był bardzo młody i miał tzw. gorącą głowę – był bardzo ognistym perkusistą i również bardzo ognistym człowiekiem, co powodowało różne napięcia w grupie. W pewnym momencie, w środku trasy, Scott zagroził, że jeśli nie damy mu więcej pieniędzy, on wraca samolotem do domu, po prostu. Sęk w tym, że nie mieliśmy żadnych pieniędzy. Gdy wróciliśmy wiedziałem, że chcę zwolnić Scotta, że nie dam rady już z nim współpracować. W międzyczasie, w trakcie trasy, Scott razem z Benem (McMillanem, wokalistą, przyp.red.) zaczęli pisać piosenki do osobnego projektu, który przerodził się później w Gruntruck. Ja i Jack w tamtym momencie nic o tym nie wiedzieliśmy. Kiedy zwolniliśmy Scotta, ten razem z Benem utworzyli Gruntruck, ja i Jack natomiast zastanawialiśmy się czy mamy jeszcze energię do tego, aby ciągnąć to dalej. Ponieważ wszystko było z wielu względów dość trudne, nie planowaliśmy, że będziemy jeszcze działać w zespole. Jack wydał solową płytę Endino’s Earthworm, ja nagrałem płytę z Helios Creed – The Last Laugh, w wytwórni Amphetamine Reptile. Zdecydowaliśmy się zrobić sobie przerwę na czas niekreślony.

Co spowodowało reaktywację?

Jack miał wystąpić na jednym gigu, razem z Melvins, w kwietniu 1990 roku i potrzebował basisty. Nauczyłem się więc kawałków z Endino’s Earthworm i zagraliśmy razem. Barrett Martin usiadł za bębnami. Świetnie się tam bawiliśmy. 2 miesiące później zdecydowaliśmy się reaktywować zespół, z Barrettem na perkusji i ponownie Benem na wokalu. Zagraliśmy pierwszy koncert w tym składzie w czerwcu 1990 roku i następnie pojechaliśmy w trasę po zachodnim wybrzeżu. Myślę, że album, który nagraliśmy z Barrettem – 1000 Smiling Knuckles – był najlepszą rzeczą, jaką kiedykolwiek zrobiliśmy. Byliśmy na scenie już około 6 lat, wreszcie wszystko zaczęło się na tyle dobrze układać, że właściwie mogliśmy zacząć żyć z grania, ale nadal było dużo ciężkiej pracy przed nami i co więcej, nadal było dużo napięć pomiędzy mną a Benem. Kreatywnie, artystycznie Ben i ja chcieliśmy robić wszystko inaczej – on chciał tworzyć w stylu Gruntruck, ja chciałem abyśmy pozostali zespołem, który robi bardziej śmiałą muzykę, który wciąż przekracza granice. Finalnie więc zdecydowałem się odejść z grupy. Było to na początku 1991 roku, mniej więcej w tym samym czasie, kiedy ukazał się album 1000 Smiling Knuckles. Mój ostatni koncert ze Skin Yard miał miejsce jakoś w lutym, a w kwietniu zespół grał już pierwszy raz na żywo z nowym basistą. Ostatni koncert w Seattle grupa zagrała we wrześniu, po czym pojechali w stosunkowo krótki – około 4-tygodniowy – tour po Stanach. Ostatni koncert w USA zagrali w październiku, po czym pojechali w miesięczną trasę po Europie. Ostatni europejski koncert, który miał miejsce w listopadzie, był ostatnim koncertem, jaki zespół kiedykolwiek zagrał. Po powrocie z trasy nagrali jeszcze kawałki, które później stały się ostatnią płytą grupy – Inside The Eye.

Album, który został wydany mniej więcej półtora roku po tym, jak zespół się rozpadł.

Wiesz, zespoły są jak małżeństwa, tylko bardziej skomplikowane bo nie jest to związek dwojga ludzi, a czworga czy pięcioro. Kiedy masz tyle osobowości, często bardzo silnych, to powstaje wiele trudności. To jest powód, dla którego często zespoły nie wytrzymują ze sobą nawet tyle lat, co Skin Yard. Jeśli możesz zarabiać na graniu i całkiem dobrze z niego żyć jest łatwiej, bo nie musicie być ze sobą cały czas. Np. Pearl Jam – oni nie są ze sobą non stop, prawda? Co kilka lat zbierają się, nagrywają płytę, jadą w trasę, a potem każdy idzie w swoją stronę, spędza czas ze swoją rodziną. To wiele ułatwia. Ale ostatecznie myślę, że nie ma takiej rzeczy, która utrzymałaby Skin Yard razem przez tak długi czas. Próbowałem parę razy stworzyć coś z Jackiem, może z innym wokalistą albo w ogóle z nim na wokalu, ale on za każdym razem mówił: “nie chcę reaktywować Skin Yard jeśli mamy być do kitu. Ostatnie moje wspomnienia dotyczące naszego zespołu to, że odeszliśmy będąc u szczytu formy – zarówno w tym jak pisaliśmy, jak również w tym, w jaki sposób graliśmy. Co jeśli reaktywujemy zespół i okaże się, że będziemy okropni? Wtedy to będzie moje ostatnie wspomnienie”. I ma rację, to dobry powód. Niemniej, Jack i ja nadal jesteśmy blisko, często ze sobą rozmawiamy, więc nie zdziwiłbym się, gdybyśmy któregoś dnia nagrali jeszcze coś wspólnie. Nie sądzę abyśmy mieli jeszcze grać razem koncerty, ale być może byłby to jakiś muzyczny projekt, myślę, że to jest całkiem realne.

Rozumiem czemu odszedłeś ze Skin Yard, ale czemu zrezygnowałeś z muzyki w ogóle? Ponieważ już od tylu lat nie grasz, zgadza się? Nie tęsknisz za tym?

To prawda i to jest dobre pytanie. Swój pierwszy od 27 lat koncert zagrałem jakieś 2 lata temu, z przyjaciółmi z okolic zatoki San Francisco i była to niezła zabawa. Przygotowywałem się także do grania z kilkoma osobami tu z pustyni i chcieliśmy zrobić kolejne koncerty, ale wtedy wybuchła pandemia i COVID wszystko ukrócił. Żeby jednak odpowiedzieć na Twoje pytanie – 1000 Smiling Knuckles było dla mnie czymś najbliższym albumowi idealnemu. Trudno mi było sobie wyobrazić, że będę jeszcze kiedyś w stanie zrobić coś równie dobrego. Wszystko w tej płycie jest doskonałe, to są najlepsze utwory, jakie kiedykolwiek napisaliśmy. Było też coś wyjątkowego pomiędzy mną a Jackiem, gdy razem pisaliśmy kawałki, stanowiliśmy bardzo zgrany team. Trudno mi sobie wyobrazić żebym miał jeszcze kiedykolwiek, z kimkolwiek innym, mieć taki rodzaj chemii, magii. Z tamtym albumem poczułem, że osiągnałem wszystko, co w muzyce chciałem osiągnąć. Nie chciałem zaczynać niczego nowego tylko po to, żeby się zawieść. 20 lat zajęło mi dojście do punktu, w którym zdecydowałem, że ok, mogę coś jeszcze zrobić, pewnie nawet nie tak dobrego… bo jeśli stworzę coś nowego, to będzie to w tej chwili tak inne, odmienne, że nie będzie to miało już żadnego znaczenia. I dużo myślę o tym, żeby znowu zacząć grać, ale nie sądzę, aby to miał być zespół, może bardziej jakiś projekt. O ile granie sprawia mi dużo frajdy, muszę przyznać, że nie lubię jeździć w trasy koncertowe (śmiech). Poza tym, jestem już znacznie starszy niż byłem, gdy opuszczałem Skin Yard. Gdy grałem ostatni koncert z zespołem nie miałem nawet 30 lat, w nadchodzące lato skończę natomiast 60. To było połowę mojego życia temu. Nie do wiary! Jestem prawie pewny, że jeżdżenie w trasy nie jest już takie fajne, kiedy jesteś stary, ale zobaczymy. Nadal mam swój bas.